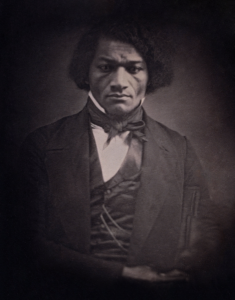

Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery in Maryland in 1838. Just six years later, at the age of twenty-six, he was invited by abolitionists to speak against slavery in Independence Square, in the shadow of the building where independence was declared. There is no known text of his speech, but two local newspapers covered the event: the Philadelphia Public Ledger and the anti-slavery paper the Pennsylvania Freeman. Later in his career as an anti-slavery activist, Douglass stressed similar themes in his well-known address, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Frederick Douglass Timeline (Library of Congress)

Philadelphia Public Ledger, August 19, 1844

Address on Slavery– About two hundred persons, about one third of whom were colored, assembled in the Statehouse yard, on Saturday evening, to hear an address delivered by Frederick Douglass, a man of color, formerly a slave. His address was interesting and of an excellent style of composition, delivered in an easy, fluent manner. He preached a sermon supposed to be delivered at the South by a master to his slaves to which the relative duties of the master and slave were given in a bitter strain of sarcasm. The opinions expressed by him were, of course, not approved of by all present, and at times some symptoms of disapprobation were apparent; but the applause of the majority drowned the dissenting voices. He was brought to rather an abrupt conclusion by the preparations for closing the square, at about quarter after 7 o’clock.

Pennsylvania Freeman, August 22, 1844

Meeting in the State House Yard

As there has been a good deal of expression in the community lately against mobs, and a strong determination manifested on the part of the city authorities to preserve the peace at all hazards, it was considered by some of our friends a good time to carry out a purpose for some time cherished, to hold anti-slavery meetings in the House Yard. Accordingly, Frederick Douglass consenting to be the speaker, an appointment was made by placards and through the newspapers, for Saturday afternoon last, a 6 o’clock. Considerable apprehension was felt by some as to the result, but those who took the responsibility of making the appointment were confident that the public feeling was such as to prevent anything like disturbance. This expectation was happily not disappointed. At the hour designated, a goodly company, both in point of numbers and character, and embracing some of both sexes, were in attendance, and Frederick took the stand. At first he seemed embarrassed and spoke with some hesitancy; but soon his embarrassment disappeared; his heart began to play, and he poured forth a stream of glowing thought and thrilling eloquence, which, coming from and unlettered colored man, seemed to many of the audience utterly amazing. They could scarcely believe him when he said that he was still a slave, and liable at any moment, under the constitution and laws of the country, to be sent back to hopeless bondage. How a man not six years freed from the yoke, and never having been, as he said, a single day to school in his life, should exhibit such a command of language and force of thought, they were utterly at a loss to imagine. All listened with deep attention, and the only interruption we heard of the quiet of the meeting arose from the hearty clapping of hands which every now and then broke in upon the speaker and betokened the feelings of the audience.

The stand which Douglass occupied was close by the old Hall in which the Declaration of Independence was adopted, and he made one or two allusions to this circumstance with thrilling effect. He gave them, also, his, “Slaveholder’s Sermon,” and, full of cutting sarcasm as it was, it was received with enthusiastic applause. He only spoke for about an hour, orders having been given, as a precaution against a riot, to close the gates at 7 o’clock; in an unnecessary measure, as little or no disposition was manifested, unless it was by the police officers themselves, to make any disturbance. Some of these fellow, how ever, seemed quite uneasy that the meeting was going off so quietly, and they were observed going through the crowd, muttering their curses, and expressing themselves in such a way of the speaker and the meeting, as under other circumstances would have probably raised a mob. Their behavior was noticed and condemned by many of our most respectable citizens, as it has often been before on similar occasions. One person, not an abolitionist, remarked to us after the meeting that Philadelphia certainly had the rowdiest police-men that ever infested any city. This is a prevailing opinion among a large portion of our citizens, and should claim the attention of his Honor the Mayor. It is in vain that we hope for the preservation of order in our city so long as we have a set of police-men appointed for that purpose. …

[…] It turns out that Douglass also gave a speech on the State House lawn many years earlier, in August 1844, which was also reported by local papers. As we can see, Douglass was right to warn the other delegates about bad publicity if he was shunned by the Convention, since his public appearances had been newsworthy items for years. News reports and reviews of the earlier speech are now hosted on the Independence Hall website, which the lady at Independence Hall welcome center kindly directed me to, and you can read them here. […]